My eulogy for my mother, Ruth Stregevsky,

delivered September 4, 2013, at her funeral

We are told by medical science that you’re five times as likely to live another year if you chat with a stranger while waiting for the doctor to see you. By this reckoning, we can safely assume that my mom is alive and kicking.

That her spirit lives on, there can be no doubt. Look around you: You’d think we’re here to remember a fallen hero.

And in a sense, we are. Ruth Rose Lehrer Stregevsky—Jewish name, Rivka Rochel—will be remembered as the consummate communitarian. And not just among Jews. Through her Christmas honey cakes, she nourished the spirits of her mailmen and garbage men. Through her bread crumbs, she nourished her feathered friends. Indeed, her 1963 letter to the editor, “Feed the Birds,” marked Ruth’s entry as a writer in public life.

Ruth's second letter to the editor about feeding birds.

And for half a century, public life remained her natural habitat. From the waiting room to the delivery room to the voting line, my mother reached out to strangers, and they to her. She was a lover at large. To her, there were no strangers; only friends she had not yet met. If Ruth had been trapped on an elevator, the riders would have asked their rescuers, “Can you come back later?” That’s how quickly she touched lives.

In her ninety-one years, my mother touched many lives, and many lives touched hers. Like Pal Joey, she would often say, “I could write a book.” And through her words and her deeds, she did. But her book remains unfinished. So today, let us together write the final chapter—the dénouement—of the Book of Ruth.

A life of compassion

In English, the word “ruth” means compassion for another being’s misery. In Hebrew, we’d say my mother had rach-MUH-nis. Long before affirmative action, she would go out of her way to hire handymen who were minorities. Once, in the late 1970s, our home was being painted by a crew of Russians, fresh off the boat. Their supervisor did not have their interests at heart. “How much are you paying them?” she asked him. “Six dollars an hour,” he assured her—good money, in those days. When they finished, my mom tallied their hours. She paid each worker his due, and paid their supervisor the balance. That’s how she ran her home.

A life of public service

But home was just her base station. When her children’s school needed volunteers, she enlisted, writing letters, penning poems, baking cookies. When a candidate or a cause needed signatures, there was Ruth, clipboard in hand, mouth in gear.

During the 24 years she spent raising her children, my mom found time to give to her community. But she would give even more in her autumn years. In her sixties and seventies, she was the playwright of choice for the Jewish Center seniors. There, her latent talents as a writer and actress reached full bloom. In more than a dozen musical shows, Ruth’s fetching scripts and guileless lyrics raised thousands of dollars while helping scores of seniors feel valued and young.

Speaking of guileless: In 1995, I told my mom I was about to propose to my second wife. My mom—who had never met Lina—replied, “Uh, Paul, have you seen her without makeup?” Who but Ruth could get away with that?

As Ruth entered her eighties, she stopped writing new plays. But she didn’t stop serving the Jewish Center seniors. Each week, they would look forward to her discussion class, The Think Tank. To prepare fresh material for each class, my mom would spend 10 to 15 hours. The hours took their toll, and I urged her to retire. But she wouldn’t hear of it. “They’re counting on me,” she’d explain.

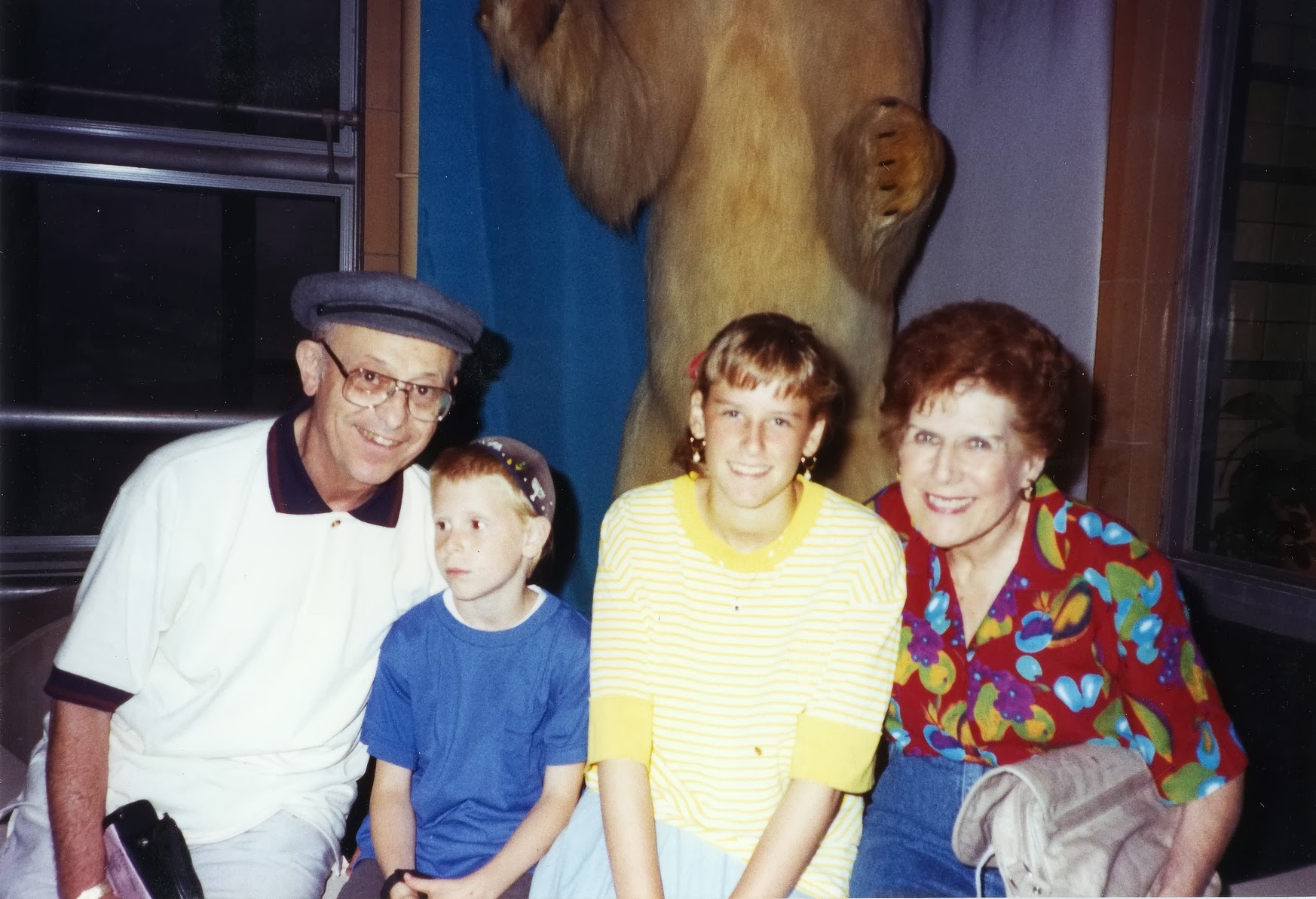

Sam and Ruth (1970s?)

Devoted wife

I could speak volumes about Ruth’s marriage to my father, Sam. But there’s little I could say that you don’t already know. Their marriage was an open book, and whatever they did, they did together. They volunteered together. Prayed together. They even entertained audiences together: Sam with his singing, Ruth with her stand-up comedy. She was the yin to his yang: she, the emotive romantic; he, the laconic scientist. Together, they raised two sons, a daughter, and a succession of cats. And for Ruth, raising the kids, and the cats, was not just a career; it was a calling.

Long-suffering mother

With three growing children, my mom took motherhood seriously. She devoured parenting advice, from televised talk shows to newspaper columns and books. But no expert could prepare my mother for the difficult middle child who stands before you today.

Indeed, when I was 23, I set up a first date with my Susan, my first wife. I giddily informed my mom. And my mom replied, “For G-d’s sake, Paul, don’t antagonize her.”

When I was 14, my mom asked Barry and me, “What are my three worst flaws?” My older brother had the good sense to say nothing. But our mom insisted we answer. “I won’t get angry,” she promised. I think you see where this is going.

“OK, then,” I offered. “One, you’re overly protective. Two, you push food. And Three, you’re not always rational.”

My mom’s response was classic Ruth: “And you're perfect?”

Image credit: zigzagmtart / 123RF Stock Photo

A year later, she began serving us cooked carrots, from Belgium. Sold in glass jars, these fancy, finger-sized veggies were not your garden-variety produce. Neither was their price. After 2 months, I said, “Mom, let’s go back to raw carrots. They cost less. They taste better. They’re better for us. And they’re easier to prepare. So what’ll it be: Belgian carrots? Or raw?”

“Belgian,” she said.

“Why?” I demanded.

“Because,” she explained.

“But that’s not logical!” I protested.

“Logic, logic, logic!” she sighed. “I can’t give you logic, Paul; I can only give you love.”

A lover at large

Showing love is what Ruth did best. Her children never wanted for self-esteem. Experts will tell you that’s a good thing (though Lina will tell you that in my case, it may have been too much of a good thing).

When I was twelve, we had a short-haired cat. Delilah would curl up on the Cincinnati Post as my mom tried to read it. And there, Ruth and cat would remain, till cat decided to move on. “Mom,” I said, “you love that cat too much.”

“There’s no such thing,” my mom replied, “as too much love.”

Closing the book

Ruth has been buried next to Sam.

My mother passed too soon to be remembered in next year’s Book of Life. But as long as her name means rach-MUH-nis, she will be remembered in The Book of Ruth. In a few minutes, we will proceed to the cemetery, where we’ll close that book. But before we do, let us write one last chapter: The epilogue.

All the world’s a stage. An aspiring actress, my mom was always on stage, eagerly playing a range of roles. But which role defined her? Devoted Wife, or Doting Jewish Mother? Political Activist, or Playwright? Community Volunteer, or Comedienne?

The answer, if we’re honest, may be Comedienne. Ever the cut-up, Ruth was often likened to Lucille Ball. If not for the War, who knows? We may have tuned in to watch “I Love Ruth.” Imagine: Hollywood would have paid Ruth to be Ruth! Inside her was an actress who missed the stage. I often wondered how heavy were her regrets.

I caught a glimpse of these regrets in 1968, when my mom was 46. On the radio, Glen Campbell was crooning his latest hit, “Dreams of the Everyday Housewife.” My mom was washing dishes. And as her hands scrubbed, her hips swayed to Chris Gantry’s poignant lyrics:

♫ She picks up her apron in little-girl fashion

As something comes into her mind,

Slowly starts dancing rememb’ring her girlhood

And all of the boys she had waiting in line—

Oh, such are the dreams of the everyday housewife

You see ev’ry`where any time of the day;

An everyday housewife who gave up the good life for me… ♫

Glenn Campbell’s studio recording of Chris Gantry’s Dreams of the Everyday Housewife

But the big reveal came three years later, as we sat before our black-and-white television, watching Masterpiece Theater. A man in his fifties was shedding tears. His wife asked, “Dear, why are you crying?” And he answered, “I’m crying…for my lost youth.” Soon, my mom joined him. “What’s wrong?” I asked. “Oh, Paul,” she cried, “I miss my lost youth.” It would take a quarter-century, and a birthday cake that bore the digits Four-Zero, before I understood how stealthily our youth slips away.

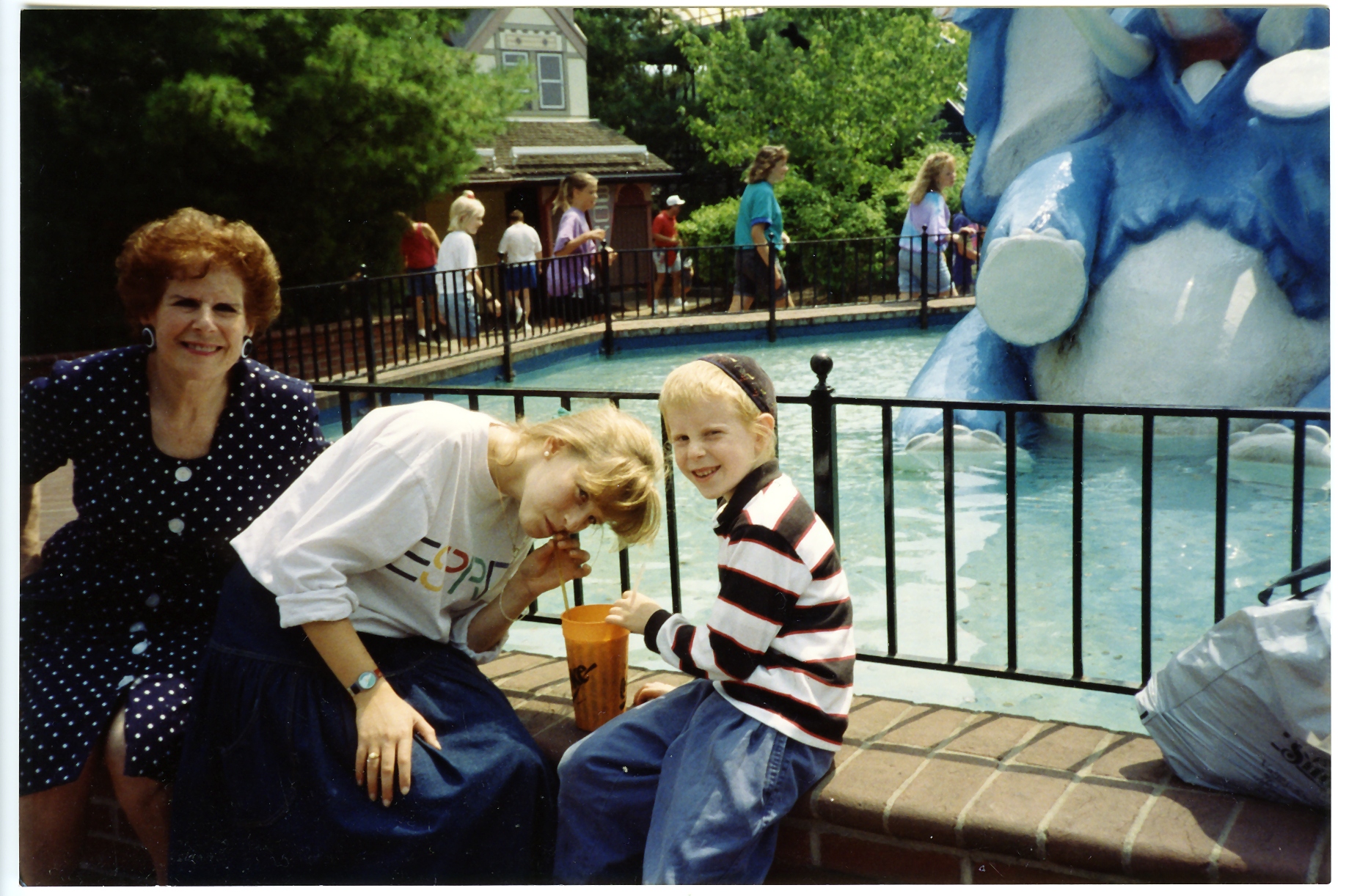

My mother slipped away with her youthful spirit intact. I believe she knew this. I also believe that in the end, she bore few regrets. Though far from rich, she had led a rich life. She’d raised good children and lived to see them do likewise. To the end, her six grandchildren—the three who shared her blood, and the three who did not—remained her proudest legacy. (Click the photo to see more images of Ruth with her grandchildren.)

If I know my mother, she’s already building a new legacy. In the waiting room for Heaven, she’s making new friends, holding court with her stories, jokes, and songs. When the gatekeeper calls their names, don’t be surprised if they answer, “Can you come back later?”

-----------------

See also these tributes:

Dearest Bubbe by granddaughter Sophia Yasgur

Dearest Bubbe Ruth by granddaughter Chana Sutofsky

Dear Bubbe by grandson Nachum Stregevsky

Ruthie Baby by son-in-law Howard Yasgur

Ruth’s funeral service (YouTube video), with all these tributes

and “Dear Bob”: My Mother’s 1945 Letters to an RAF Serviceman.